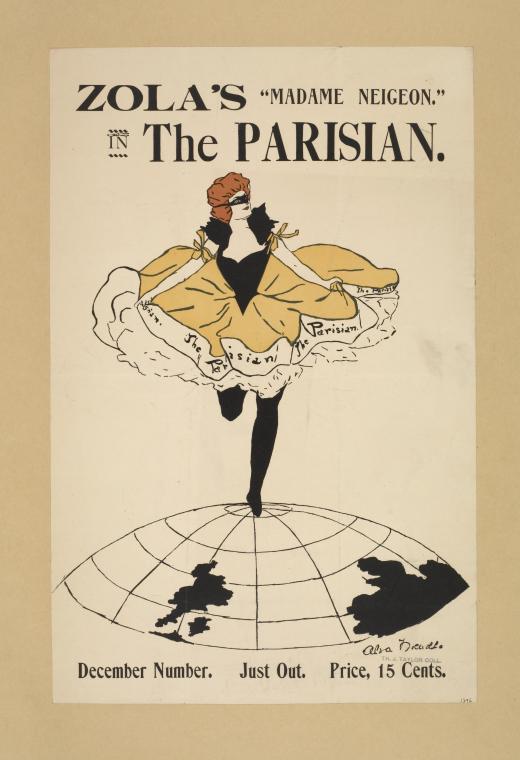

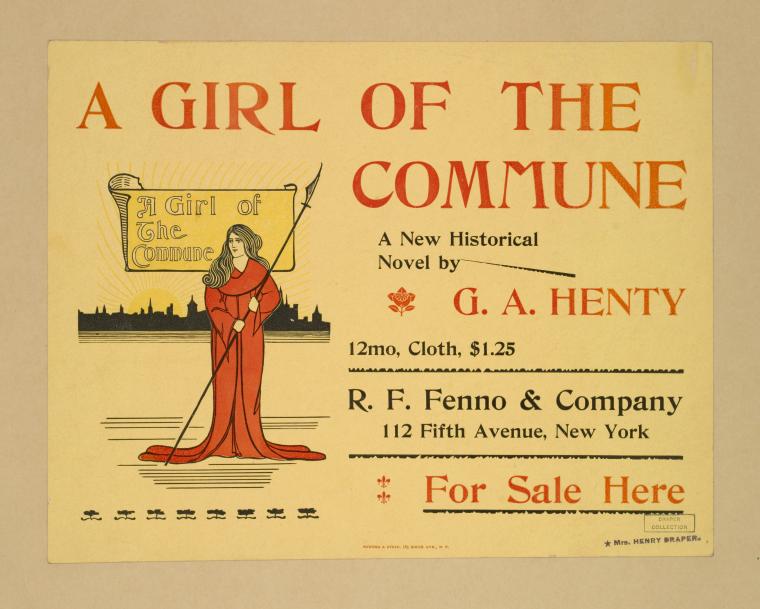

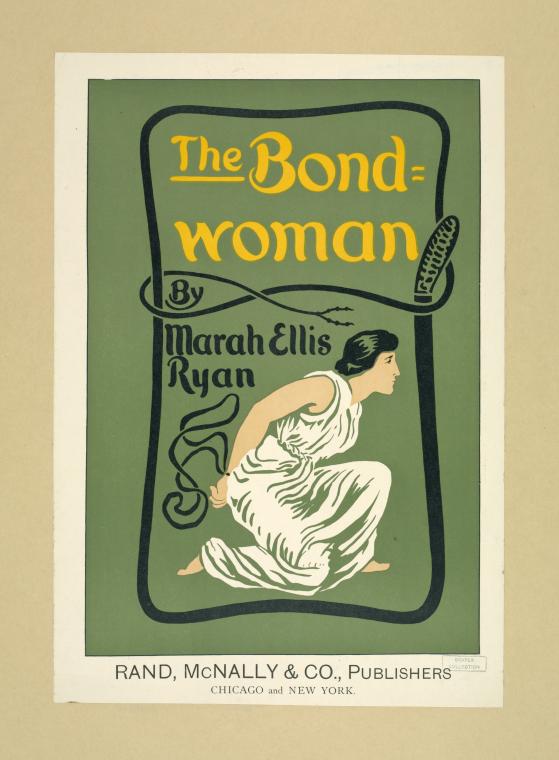

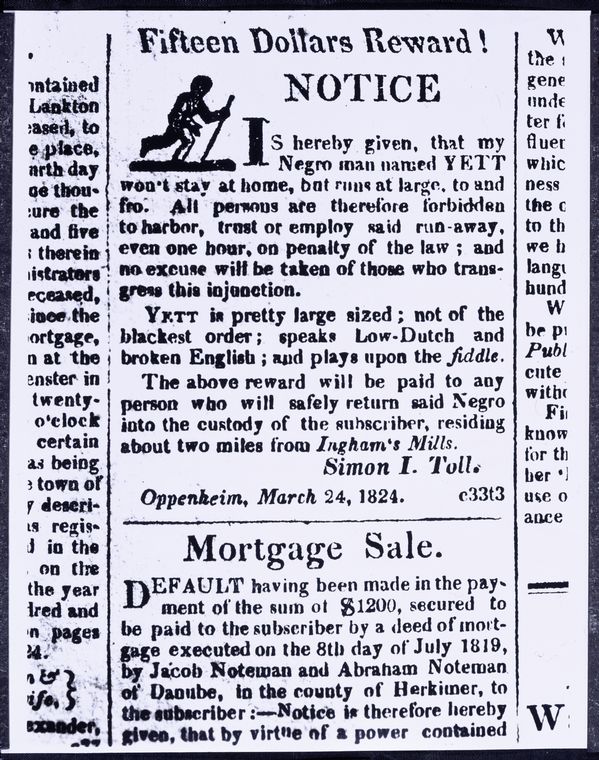

Today’s post is geared toward foreign language instructors, who are tasked with finding creative ways to make things like grammar and vocabulary come alive for their students. In language classes, it’s common to have students try to describe things like their ideal outfit or favorite food to build their skills. Why not use digital collections as material for such assignments to challenge students and expand their vocabulary?

You could project or give out copies of the images – should we ever see the inside of a classroom ever again – and have students work in groups to describe what they see to the class, but I suspect that only works at advanced levels and can easily overlook shy students. In an introductory language course, I would make this a take-home writing assignment, so students can take the time to look up and absorb new vocabulary. This means they can “write-to-learn” rather than write for evaluation by their instructor; another component to this assignment would be to have the students read what they’ve written to the class, so they can practice pronunciation and so forth. In a remote learning situation, I would send the students a folder with images culled from these digital collections, have them write a description of what they see, and hand it in to me or read it to the class as part of their nebulous participation grade. I could also see this working as an extra credit opportunity.

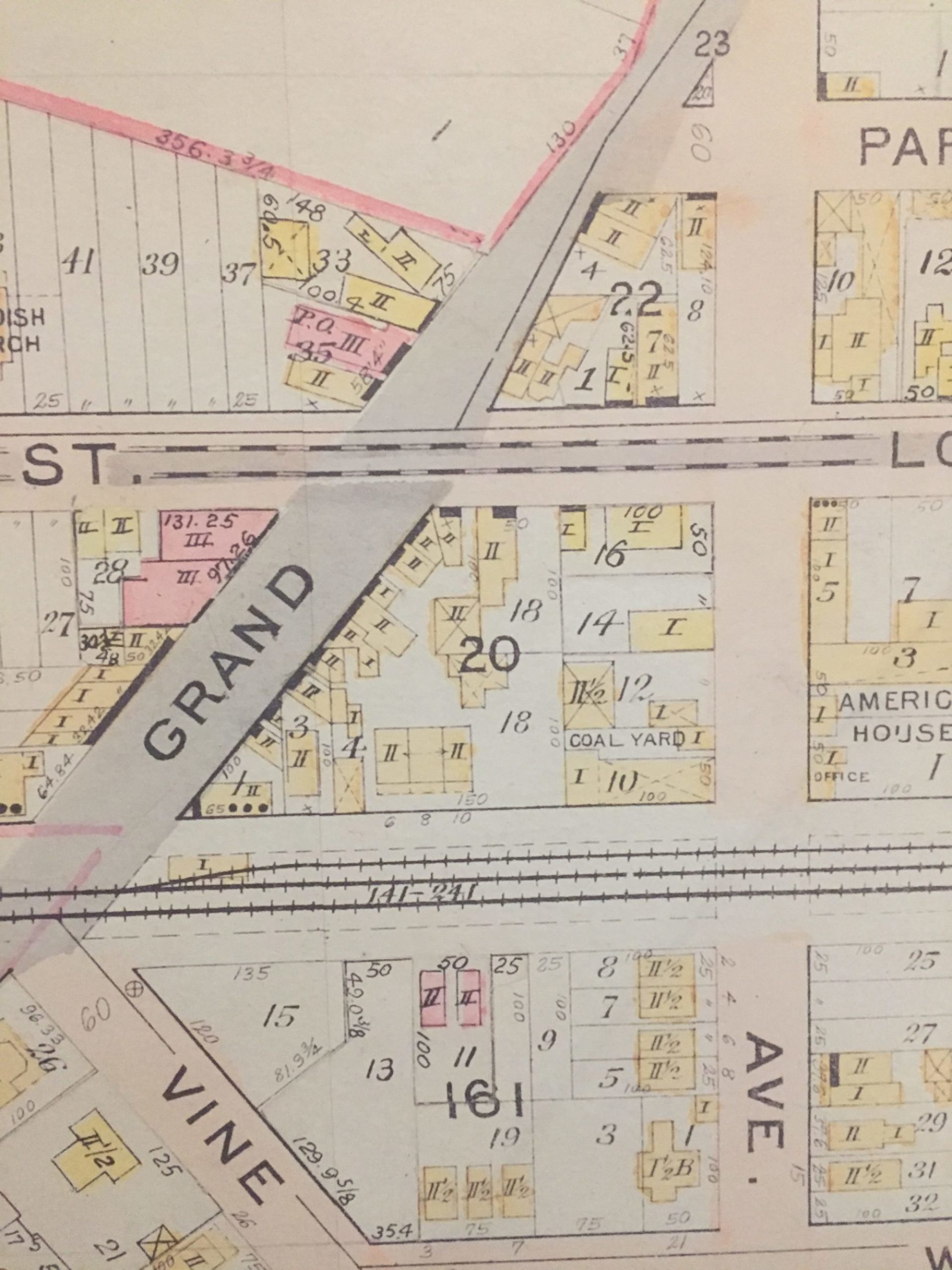

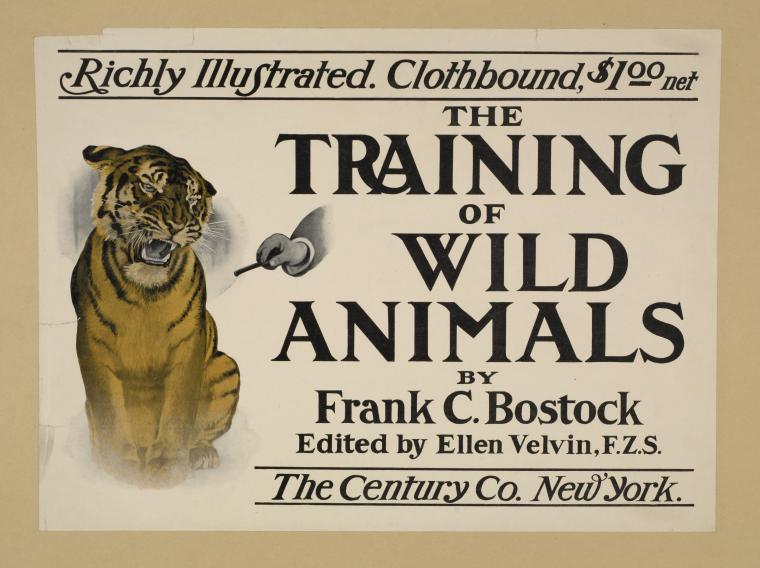

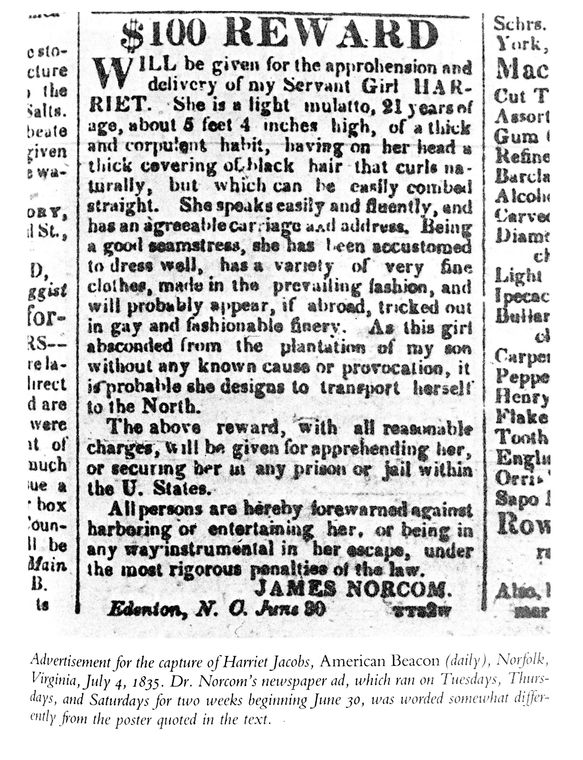

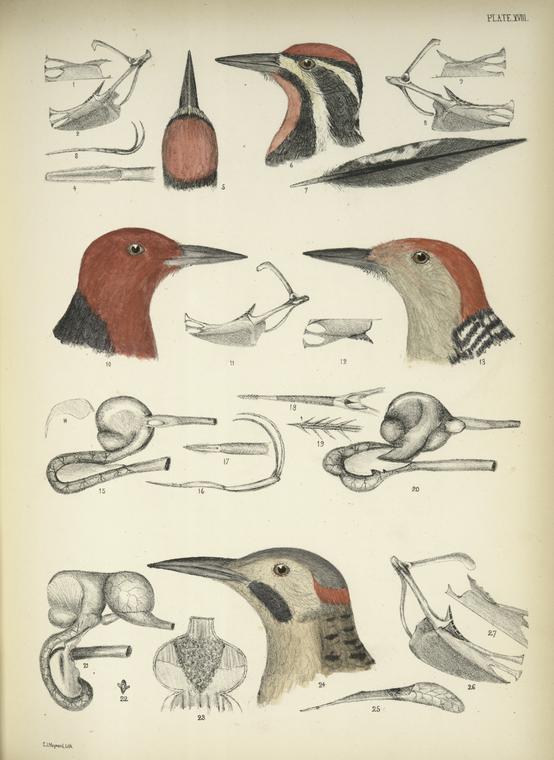

I would assign a few of these over the course of a semester, and try to align the images I choose with the material from the unit we’re covering, so students can build on a type of vocabulary and hopefully create mental associations for themselves. So, for example, if a language unit deals with nature or animal-related vocabulary, I would try zoological illustrations: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/birds-of-eastern-north-america-with-original-descriptions-of-all-the-species#/?tab=about&scroll=15

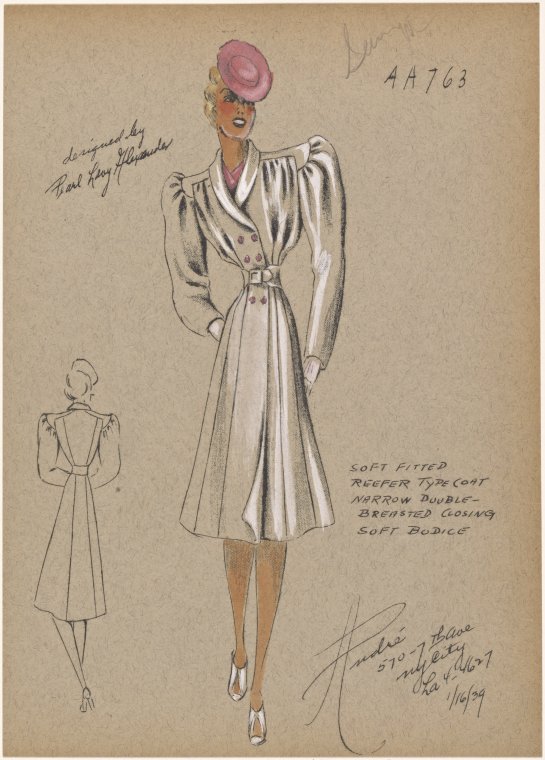

For a unit on clothing, I would use midcentury fashion illustrations: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/andr-fashion-illustrations-from-nypls-picture-collection#/?tab=navigation

For a unit on cities, try this collection of vintage photos of New York: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/collection-of-photographs-of-new-york-city-new-york-state-and-more-by-max#/?tab=navigation&scroll=42